The Original Meaning of Religion

Religious freedom is a crucial right in the United States that affects the ordinary beliefs and practices of individuals and communities across the nation. The First Amendment enshrines that right in the Constitution, stating "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof."

But what exactly is a religion, for purposes of the First Amendment? Under current legal precedent, the definition is far from clear.

This question is not one of mere theoretical curiosity: How courts define religion determines which activities will receive protection from government interference. If that definition is overly broad and amorphous, as it is under current precedent, the safeguarding of religious freedom will allow all kinds of non-religious ideologies, from Satanism and New Atheism to the "wokeism" of the social-justice left to the creeds of the satirical Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster, to co-opt and abuse the right to free exercise of religion, rendering the freedom of religion all but meaningless.

To take the original meaning of the First Amendment seriously is to recover a constitutional order that protects religious exercise. Only once the definition of religion has been sorted out and clarified can the courts coherently analyze whether particular conduct is protected by the Constitution.

A MUDDLED DEFINITION

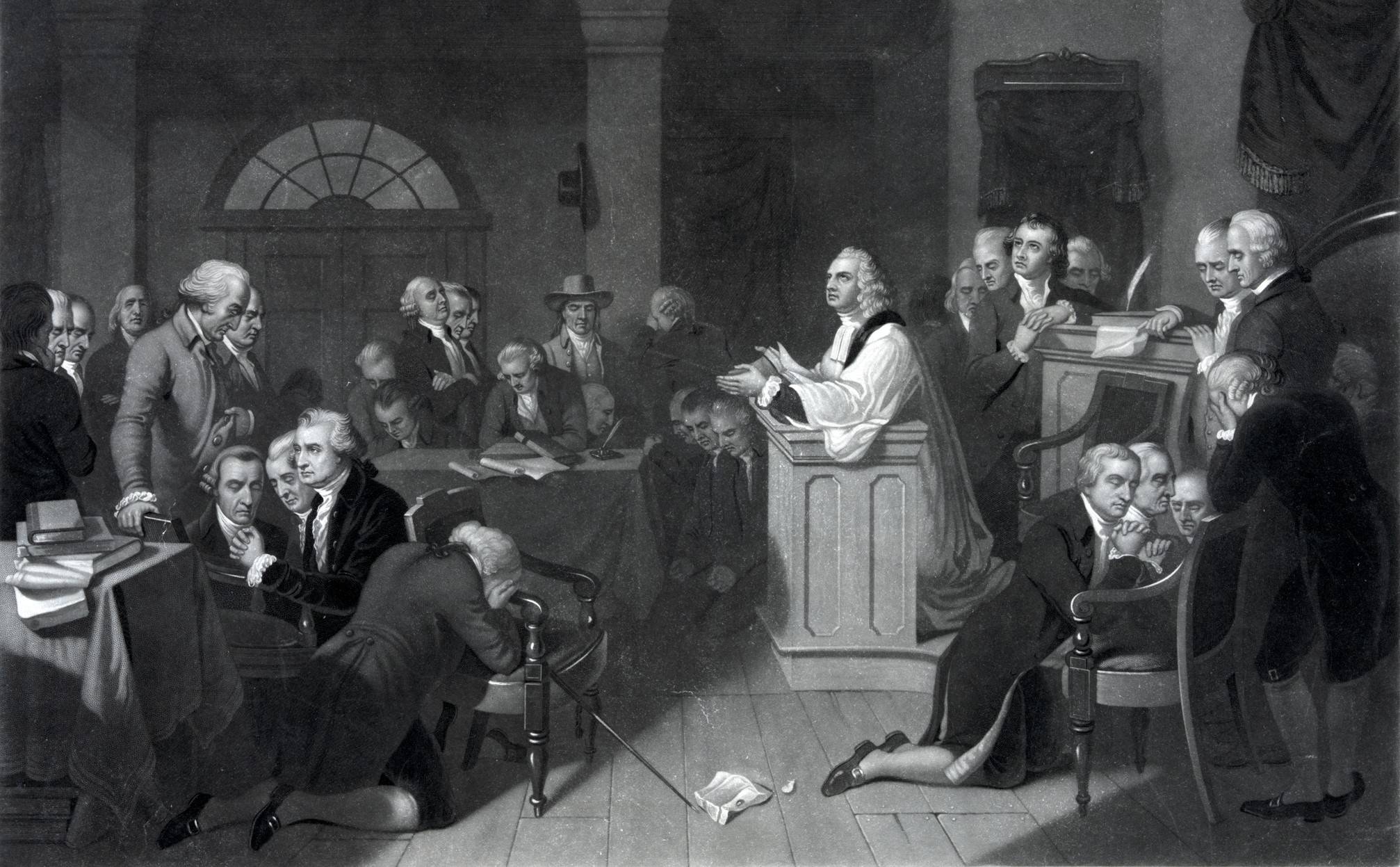

When the Bill of Rights was drafted in 1789, there was little debate over the First Amendment's religion clauses. And from the time of the founding until the mid-20th century, the Supreme Court held a fairly consistent view of what constituted a religion for the purposes of the amendment.

One of the first cases to outline the boundaries of the term, Reynolds v. United States, was decided in 1879. There, a unanimous Supreme Court briefly characterized religion as "the duty we owe the Creator." Eleven years later, in Davis v. Beason, the Court expanded on this definition, characterizing religion as "one's views of his relations to his Creator, and to the obligations they impose of reverence for his being and character, and of obedience to his will." A similar definition appeared in the 1931 case United States v. Macintosh, which stated that the "essence of religion is belief in a relation to God involving duties superior to those arising from any human relation." Notably, Reynolds, Davis, and Macintosh all identified a Creator, as well as the duties, obligations, reverence, or obedience owed to that Creator, as key components of religious faith.

Yet as America grew more diverse over the course of the 20th century, the Court began to reconsider this standard. Its first departure occurred in 1944, in United States v. Ballard. There, the Court observed that the right to religious freedom

embraces the right to maintain theories of life and of death and of the hereafter which are rank heresy to followers of the orthodox faiths....Religious experiences which are as real as life to some may be incomprehensible to others.

In other words, a religion's practitioners may qualify for constitutional protection even if they do not follow traditional religious tenets.

A second, more explicit departure occurred in Torcaso v. Watkins in 1961, when a unanimous Court held that a state may not "aid those religions based on a belief in the existence of God as against those religions founded on different beliefs." Among the examples of non-theistic religions it listed were Buddhism, Taoism, ethical culture, and secular humanism.

In acknowledging that a religion does not necessarily have to involve God or any other deity to qualify as such under the First Amendment, Torcaso upended the Court's religious-clause precedent. The Supreme Court has struggled to draw a line between religion and non-religion ever since.

The leading case on the matter is now United States v. Seeger, in which the Court considered a constitutional challenge to the Universal Military Training and Service Act. That statute exempted from the military draft anyone who, by reason of his "religious training and belief," was forbidden from participating in war. It went on to define religion as "an individual's belief in a relation to a Supreme Being involving duties superior to those arising from any human relation."

The lead respondent in the case, Daniel Seeger, had been convicted for refusing to register for the draft. Seeger was a pacifist and an agnostic, and because he did not profess a belief in God, he was denied the exemption. He filed suit challenging the decision, arguing that the statute's definition of religion, if interpreted narrowly to include only those religions that recognize a traditional God, was unconstitutional.

The question in Seeger hinged on whether the term "Supreme Being," as used in the Universal Military Training and Service Act, was broad enough to include religions that did not recognize an orthodox notion of God. In its majority opinion, the Court reasoned that Congress had included the term "Supreme Being" in the statute not to confine the definition of religion to theistic ideologies, but to distinguish religious beliefs from those motivated by political or philosophical views. It then announced what it called an "objective" standard: "[T]he test of belief 'in a relation to a Supreme Being' is whether a given belief that is sincere and meaningful occupies a place in the life of its possessor parallel to that filled by the orthodox belief in God."

Curiously, the Seeger Court's definition of religion rejects traditional definitions of the concept while using them as the benchmark for what constitutes a religion. In doing so, it begs the very question asked. The standard is also nonsensical: It identifies as a religion a belief system that is decidedly not a religion.

Neither of these concerns prevented the Court from doubling down on its commitment to an expansive definition of religion in another conscientious-objector case, Welsh v. United States. The petitioner in Welsh asserted that he qualified for a conscientious-objector exemption even though his beliefs were not religious in the traditional sense of the term. The Supreme Court agreed, holding:

If an individual deeply and sincerely holds beliefs that are purely ethical or moral in source and content but that nevertheless impose upon him a duty of conscience to refrain from participating in any war at any time...such an individual is...entitled to a "religious" conscientious objector exemption.

This is a remarkably broad definition of religion. In Seeger, the Court explicitly excluded philosophical and personal beliefs from its definition of religion. Here, the Court embraced them, resting the primary distinction between religion and non-religion not on the content of those beliefs, but on the strength with which the beliefs are held.

Just two years after Welsh, the Court appeared to backtrack. In Wisconsin v. Yoder, the Court considered a challenge to Wisconsin's compulsory school-attendance law brought by three Amish individuals who argued that sending their children to formal schooling after eighth grade would violate their religious beliefs. Writing for a unanimous Court, Chief Justice Warren Burger held:

[T]o have the protection of the Religion Clauses, the claims must be rooted in religious belief. Although a determination of what is a "religious" belief or practice entitled to constitutional protection may present a most delicate question, the very concept of ordered liberty precludes allowing every person to make his own standards on matters of conduct in which society as a whole has important interests.

He added that a belief based solely on "philosophical and personal" reasons, rather than religious ones, "does not rise to the demands of the Religion Clauses."

By exempting personal philosophies from protection, the Court's holding in Yoder would seem to have narrowed the expansive definition of religion announced in Seeger and broadened in Welsh. However, the Court ultimately sided with the respondents, finding that the Amish were entitled to religious protections based on their long history, traditions, and established way of life.

Since Yoder, the Court has largely avoided examining claims grounded in distinctions between religion and non-religion. When forced to wrestle with the matter, as in the 1981 case of Thomas v. Review Board, it has carefully sidestepped the issue, reasoning that a "determination of what is a 'religious' belief or practice...is not to turn upon a judicial perception of the particular belief or practice in question."

Thanks to these nebulous and at times inconsistent rulings, religious-freedom jurisprudence has reached a place where anyone claiming to have a serious belief system can seek and be granted legal protections for their activities, regardless of whether the beliefs are grounded in religious faith. One illustrative example occurred in the wake of Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, which overturned federal protections for abortion. In an attempt to challenge the restrictions Indiana and Idaho had placed on the practice, the Satanic Temple claimed that abortion is a religious sacrament that its practitioners must be permitted to undergo.

Should courts hold that state abortion restrictions cannot be applied to Satanists? One could argue that the Satanists are not making these claims in good faith, or that their supposed religious belief is not sincerely held. But how might courts go about testing the degree of good faith involved in a claim being made, or the sincerity of the beliefs one holds? One could alternatively assert that the government has a compelling interest in protecting life that overrides the free-exercise claim. That may be true of the Satanic Temple example, but what of claims that don't rise to the level of life and death that are nonetheless grounded in personal philosophies and policy preferences as opposed to sincere religious faith?

Acquiescing to the dubious religious-liberty claims of Satanists and others dilutes robust protections for traditional religious exercise, both public and private. More fundamentally, though, these modern standards are simply not what defined a religion at the time the First Amendment was enacted: It is religious exercise that is protected by the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment, not the exercise of non-religious or even quasi-religious belief systems. To ensure that religious protection means something, we must be able to explain why Christianity and Judaism, for example, are religions under the First Amendment, and why Satanism, atheistic humanism, and other belief systems are not.

ORIGINAL PUBLIC MEANING

When seeking the definition of a word within a legal text, the obvious place to start is with the text itself. This method of legal interpretation, known as "originalism" or "textualism," depending on the circumstances, has come to dominate the jurisprudence of federal courts, and for good reason: If a law's words do not have a fixed meaning when they are enacted, judges are left free to interpret that text as changing with the times, which undermines the rule of law itself.

Many of today's originalists prefer to emphasize the original public meaning of the text — that is, in the words of law professor Michael Stokes Paulsen, "the objective meaning the words would have had, in historical, linguistic, and political context, to a reasonable, informed speaker and reader of the English language at the time that they were adopted." Though there remain disagreements among proponents of various sub-genres of originalism, for simplicity's sake, we will use this approach.

Unfortunately, originalist interpreters will not find much to aid their inquiry in the text of the Constitution. The unamended document uses the term "religion" only once, in prohibiting the use of a religious test as a qualification to hold public office. The amendments, too, are short on explanation, providing no definition of the word and, aside from the Establishment and Free Exercise clauses, never mentioning it again.

When the Constitution's text fails to provide a definitive answer on the meaning of a term, originalists may gain some insight into what that term might have been understood to mean by expanding their search to other sources written around the same time as the text in question. Three sources in particular offer helpful clues to interpreting the First Amendment: 18th-century dictionaries, debates and writings concerning religious freedom during the time of the founding, and early case law interpreting the First Amendment. Since we have already addressed early court precedent, we will focus here on the first two sources.

To discern the meaning of any term, a natural first source one might consult is the dictionary. Samuel Johnson's Dictionary of the English Language, published in 1755, was highly influential at the time of the founding. Johnson defined religion as "1. Virtue, as founded upon reverence of God, and expectation of future rewards and punishments. 2. A system of divine faith and worship as opposite to others." The same dictionary described "divine" as "1. Partaking of the nature of God. 2. Proceeding from God; not natural; not human." From this, we can gather that religion was thought to include a system of faith, reverence and worship, and God.

Perhaps the bestselling English dictionary of the 18th century was Nathan Bailey's Universal Etymological English Dictionary. Its definition of "religion" is quite short: "the Worship of a Deity, Piety, Godliness." Another edition offered this definition: "Religion is defined to be a general Habit of Reverence towards the divine nature, by which we are both enabled and inclined to worship and serve God, after that manner which we conceive to be most agreeable to his will, for that we may procure his favour and blessing." Again, we see references to notions of "reverence," "worship," and the divine.

Of course, dictionary definitions do not provide a definitive answer to the question of what qualifies as a religion under the First Amendment. But they do give judges and legal scholars a good place to start. From these three definitions, we can begin to form the contours of the term "religion" as understood when the First Amendment was written. Simply put, religion at the time of the founding meant, more or less, a system of faith concerning God and man's relationship to God, encompassing notions of faith, reverence, and worship.

For additional guidance in discerning the original public meaning of a term, originalists often refer to outside sources written during the period in question. Legal and constitutional texts are especially useful in this regard.

When the framers drafted the First Amendment, many state constitutions contained particular protections for "freedom of conscience." The New Hampshire Constitution, for instance, stated:

IV. Among the natural rights, some are in their very nature unalienable, because no equivalent can be given or received for them. Of this kind are the RIGHTS OF CONSCIENCE.

V. Every individual has a natural and unalienable right to worship God according to the dictates of his own conscience, and reason; and no subject shall be hurt, molested, or restrained in his person, liberty or estate for worshipping God, in the manner and season most agreeable to the dictates of his own conscience, or for his religious profession, sentiments or persuasion; provided he doth not disturb the public peace, or disturb others, in their religious worship.

A similar right appears in the Pennsylvania Constitution:

That all men have a natural and unalienable right to worship Almighty God according to the dictates of their own consciences and understanding: And that no man ought or of right can be compelled to attend any religious worship, or erect or support any place of worship, or maintain any ministry, contrary to, or against, his own free will and consent: Nor can any man, who acknowledges the being of a God, be justly deprived or abridged of any civil right as a citizen, on account of his religious sentiments or peculiar mode of religious worship: And that no authority can or ought to be vested in, or assumed by any power whatever, that shall in any case interfere with, or in any manner controul, the right of conscience in the free exercise of religious worship.

In such cases, the term "conscience" had a distinct meaning, with implications for both what type of belief system was protected (conscience rights might very well have gone beyond traditional religious belief systems) and what the right actually entailed (internal belief versus conduct in the public square).

The framers had these examples on hand when they wrote the First Amendment, suggesting they were familiar with conscience rights. Indeed, when drafting the Bill of Rights, the First Congress proposed amending Article 1, section 9, of the Constitution to insert the phrase, "no religion shall be established by law, nor shall the equal rights of conscience be infringed." In the end, they did not select the term "conscience" when drafting the First Amendment. Nor did they choose near-synonyms like "philosophy," "ideology," "beliefs," "morals," or "core values," even though all of those options were available to them. Rather, they chose to protect the free exercise of religion. Clearly, something more than mere conscience was meant to be secured.

Another source that provides insight into what the term "religion" meant at the time of the founding is the Virginia Declaration of Rights. The declaration was drafted primarily by George Mason, a founding father and supporter of the Bill of Rights, with the help of James Madison. It was enacted in 1776, just as revolutionary thought and discourse were at their height. Because of Virginia's significance within the young republic and the enormous influence of the founders who both served in the Virginia state government and were involved in drafting the U.S. Constitution, the Virginia declaration's statements on religion give us an important glimpse into what the term meant in this era.

The Virginia declaration described religion and religious freedom in this way:

That religion, or the duty which we owe to our Creator, and the manner of discharging it, can be directed only by reason and conviction, not by force or violence; and therefore all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience; and that it is the mutual duty of all to practise Christian forbearance, love, and charity toward each other [emphasis added].

Here, we see a concise definition of religion that emphasizes notions of duty and God.

A third useful document, drafted nine years after the Virginia Declaration of Rights, is Madison's Memorial and Remonstrance against Religious Assessments, which contained an enlightening analysis of religious freedom. Madison began his argument therein by pointing to the "unalienable right" to freedom of religion, which, quoting the Virginia Declaration of Rights, he identified as the right to freely exercise "the duty which we owe to our Creator and the manner of discharging it." Again, the words "duty" and "Creator" appear.

The definitions provided in both Memorial and Remonstrance and the Virginia Declaration of Rights are remarkably consistent with the dictionary definitions from the 18th century, which defined religion as a system of faith encompassing reverence toward and worship of God. Furthermore, the definitions from all three of these sources are consistent with the earliest case law on the Free Exercise Clause — which, if you'll recall, defined religion as "the duty we owe the Creator" (Reynolds v. United States) and "one's views of his relations to his Creator" (Davis v. Beason).

While it is difficult to distill these various 18th-century texts into a single definition, it may be useful to make the attempt. Religion for purposes of the First Amendment can be loosely defined as the duty that we owe to God our Creator, involving worship of the divine and a set of beliefs and practices responsive to God's desire for how humans ought to live and behave.

The traditional monotheistic religions — all Christian denominations, Judaism, Islam, Sikhism — almost certainly fall within this definition. Polytheistic faiths like Hinduism are probably closer to the periphery, but it still makes sense to define them as systems that attempt to worship and respond to the divine. Atheistic belief systems (including many modern forms of humanism, but also the ancient practices of Buddhism and Confucianism) likely fall outside the scope of religion because there is no faith in or worship of a deity involved. The Satanic Temple should be excluded: An ideology that claims to be atheistic (as does the temple) fails the religion test outright.

PROTECTING OLD-TIME RELIGION

The English cardinal St. John Henry Newman once noted that he had made a particular intellectual endeavor "with the full recognition and consciousness" that he was making only "a first approximation to a required solution." Similarly, the definition of religion outlined above is hardly the last word on the matter; it is rather a "first approximation to a required solution" to the problem of how to define the term "religion" in federal law.

But with the future of the religious-freedom movement in America in peril, it is time for lawyers, judges, and scholars to start a conversation about what it would mean to take the original meaning of religion in the Constitution seriously. The subjective tests now used by courts to interpret religious-freedom law have left judges stuck trying to figure out whether a belief system looks like a religion, rather than simply asking whether the belief system is a religion.

As religious-freedom advocates continue to fight for the rights of religious believers to practice their faith, a failure to define what religion is will have troubling consequences. If additional secular belief systems find their way into a shifting, expansive, and ultimately incoherent definition of religion, courts might very well lose control of the entire religious-exemption question. It is one thing to carve out exceptions for orthodox religious beliefs; it is quite another to carve out exemptions for a growing and ever-changing group of belief systems used, at times in bad faith, to justify what are ultimately policy preferences.

There can be no coherent religious-freedom movement without a meaningful legal understanding of religion. History makes clear that protecting religious exercise was an intentional choice by the founders to defend religious belief systems and not others. If Americans today believe that the Constitution should protect non-religious ideologies, the appropriate recourse is to modify the First Amendment. Until then, it is only religion that qualifies for special protections.

Lawyers, judges, and scholars have the tools they need to recover the original public meaning of religion. And the United States currently has a Supreme Court equipped to do the serious and needed work of properly defining religion under the First Amendment. The time has come for this Court to weigh in and prevent relativism from gutting religious liberty.