How the White House Makes Policy

One of the president's most important responsibilities at the outset of his term is organizing the White House. Unlike most of the federal bureaucracy, the White House consists largely of political appointees who serve at the pleasure of the president and (presumably) represent the president's best interests.

Approximately 1,800 people work at the White House complex, but most of them are career officials in departments like the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) or the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, both technically part of the Executive Office of the President. Out of those 1,800, only a few hundred are "White House staffers" of popular imagination, as depicted in shows like The West Wing.

What do these staffers do? One veteran staffer once told me that the entire White House operation is designed to do two things: prepare the president for events, and tee up questions for the president to decide. The events side is handled by the communications, advance, public-liaison, and speechwriting teams, among others, while the decision side is handled by bodies known as policy councils. These councils, along with single-issue policy "czars," make decisions through what is called the White House policy process.

That process has a long and storied history, which, for the most part, continues from administration to administration, regardless of partisan affiliation. It is a sorting mechanism that allows administrations to triage the thousands of decisions that must be made over the course of a presidential term. If the process is working correctly, most decisions are resolved before they even reach the White House. According to one report from the Obama administration, 95% of key national-security decisions were made before reaching the cabinet-secretaries and senior-aides level; this was due largely to the aggressive efforts of national-security advisor Tom Donilon to resolve issues early in the process.

The most challenging decisions come to the White House through one of the lower, non-presidential levels of analysis. These include, in ascending order, the Policy Coordination Committee (or the Interagency Policy Committee, as it is known under Joe Biden), which is made up of special assistants to the president and non-Senate-confirmed agency representatives; the deputies level, which is run by a deputy assistant to the president and includes deputy secretaries of executive agencies; and the principals level, which is run by the White House chief of staff and includes cabinet secretaries and senior White House aides. If the decision must go to the president, it moves via decision memo or in a discussion between top aides and the president during what's known as "policy time."

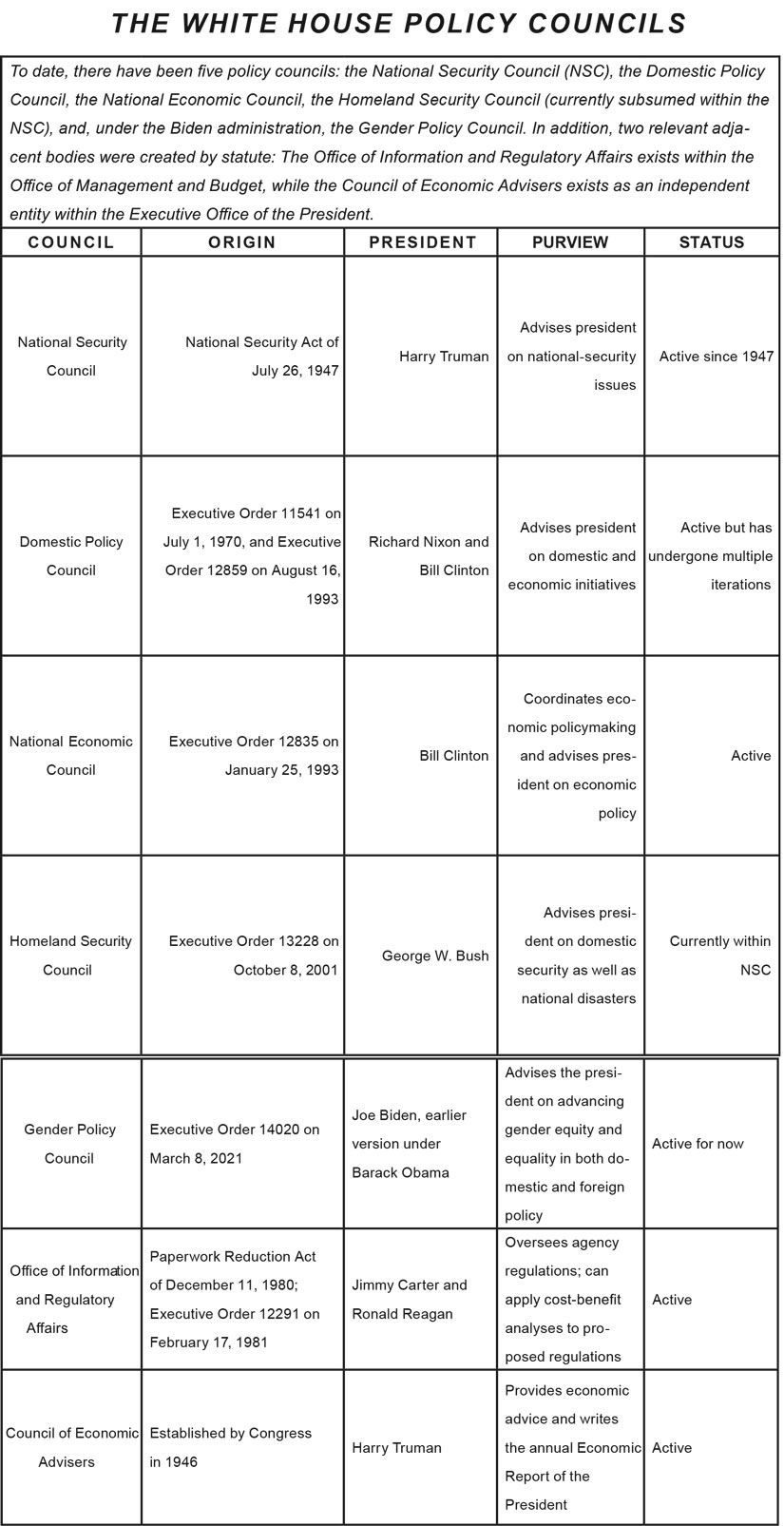

The policy councils are not set in stone: The last half-century has seen the creation and dissolution of White House councils. Yet, for the most part, they endure. The tradition they manage is complex and nowhere fully recorded; instead, it is passed on from generation to generation of White House staffers as a legacy to uphold.

Given the legacy of that process, the people involved take it seriously. Someone who acts without adhering to the proper process can be accused of committing "a process foul." In the George W. Bush White House (where I served as deputy assistant to the president for domestic policy), this was a damning accusation.

The policy process and the councils governing it are important: They determine both an administration's priorities and its method of pursuing policy goals. Even more important, however, is the continuity and stability of the process, which is essential for effective governance. As an overview of the last 70 years will demonstrate, a productive executive policy process requires stability and long-term respect for established norms. Success in pursuing key presidential priorities — from regulatory reform, to China policy, to the national debt — hinges on it.

THE NATIONAL SECURITY COUNCIL

The policy process is managed by the White House policy councils. The first of these was the National Security Council (NSC), established in July 1947 by the National Security Act. Originally, the president; the secretaries of State, Defense, the Army, the Navy, and the Air Force; and the chairman of the National Security Resources Board were the permanent members of the council. The NSC had its origins in the coordinating bodies that managed World War II, including the British Committee of Imperial Defense and American versions like the Standing Liaison Committee and the State-War-Navy Coordinating Committee. It was meant to manage foreign and defense policy with America's overarching national-security interests in mind.

The NSC was designed to have a coordinating, rather than operational, mission. Harry Truman recognized the impulse toward operations early on but quashed it, recalling: "There were times during the early days of the National Security Council when one or two of its members tried to change it into an operating super-cabinet on the British model." Early changes in 1949 helped maintain the NSC's coordinating focus: Truman placed the council within the Executive Office of the President while dropping the direct inclusion of the heads of the Army, Navy, and Air Force; instead, the Joint Chiefs of Staff would serve as an advisor to the council. Truman also limited attendance to statutory members, cutting down on the "foreigners" who were drifting into meetings and changing the closed nature of the deliberations. These early reforms foreshadowed the challenges of trying to prevent an advisory council from becoming an unwieldy bureaucracy of its own.

Perhaps predictably, the creation of the NSC led to tension with the State Department. Under President Dwight Eisenhower, the State Department retained more power in the relationship — in large part because of John Foster Dulles, Eisenhower's influential secretary of State. President John Kennedy — following the failed Bay of Pigs operation in 1961 — moved to establish more independent executive access to defense intelligence, thus elevating the NSC. This led to the creation of the Situation Room, which established a central communications office in the White House near the office of the national-security advisor. While that position was initially an executive secretary to the NSC, under Eisenhower, it became the more prominent position we know today.

The balance of power between State and the NSC changed definitively under Richard Nixon. Nixon wrote in his memoirs: "From the outset of my administration...I planned to direct foreign policy from the White House. Therefore, I regarded my choice of a national security advisor as crucial." His choice was Henry Kissinger, the most famous national-security advisor to date.

Kissinger was certainly on board with Nixon's instinct to "direct foreign policy from the White House." Before the Nixon administration even began, Kissinger and aide Mort Halperin wrote a "Proposal for a New National Security Council System" that elevated the national-security advisor over the secretaries of State and Defense. Nixon approved the memo prior to his first meetings with secretaries designate William Rogers of the State Department and Mel Laird of the Department of Defense, and the entire episode went down in history as the "coup d'état at the Hotel Pierre."

In addition to implementing structural changes, Kissinger also schemed relentlessly to diminish Rogers and keep him in the dark. Rogers eventually resigned, and Nixon appointed Kissinger as his replacement while allowing him to maintain his role as national-security advisor — the only time anyone has held both roles. It is likely to remain the only time: When Donald Trump asked Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to take on the duties of national-security advisor as well, Pompeo wisely refused, citing the Kissinger example.

When Gerald Ford took over from Nixon, he recognized that having one person in both roles was a problem. Ford stripped Kissinger of his role as national-security advisor, replacing him with Brent Scowcroft. Although Kissinger retained significant influence, he was an exception. Kissinger's efforts against Rogers diminished the secretary of State's stature and elevated the national-security advisor.

Jimmy Carter's administration exhibited a similar dynamic. Secretary of State Cyrus Vance was often flummoxed by national-security advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski, who made sure that Carter heard his voice most frequently (including on the tennis court, where they played together regularly). Furthermore, Brzezinski had the pen on interagency memos, which meant in those pre-email days that if Vance wanted to edit or change the content, he would have to leave Foggy Bottom and go to the White House, which he rarely had time to do. In these and other ways, Brzezinski used his proximity to Carter to maintain the upper hand over Vance.

In Ronald Reagan's administration, Secretary of State-designate Al Haig, who had served at the NSC under Kissinger, wanted to shift the balance of power back toward the State Department. He tried a Kissinger-like move, presenting Reagan aides with a memo that would make him the "vicar" of foreign policy. Reagan White House aide Edwin Meese put the memo in his "Meesecase" — the briefcase into which papers went, but never came out — and the idea was shelved.

Unfortunately, the NSC under Reagan became too powerful and too operational, most infamously in the Iran-Contra Affair, a semi-rogue NSC operation in which the United States tried to secretly sell arms to Iran to secure the release of American hostages and fund the Nicaraguan Contras. The scheme was exposed in 1986, creating a scandal that rocked the Reagan presidency. In the wake of the scandal, the NSC underwent major internal changes, moving away from operations and back toward its traditional coordination and advisory role.

The reforms worked, and the NSC was in a better place during the George H. W. Bush years. As historian and former NSC aide Peter Rodman wrote: "From the management point of view, the administration of our 41st president was the most collegial and smoothest-run of the presidencies we are considering." Secretary of State James Baker appreciated the changes as well, writing that, under Bush: "[W]e made the national security apparatus work the way it is supposed to." It helped that Scowcroft had returned as national-security advisor, still to this day the only person to fill the role twice.

Bill Clinton — who ran with the campaign slogan, "the economy, stupid" — subsequently tried to elevate economic issues in the NSC's purview. During his second term, under national-security advisor Samuel "Sandy" Berger, Clinton implemented a series of principles determining the NSC's focus. These principles included integrating Eastern and Western Europe while not provoking Russia, pursuing free trade, increasing attention on terrorism and narcotics, and trading with China while avoiding disputes over human-rights issues.

The George W. Bush administration saw significant infighting among Bush's team of experienced national-security players, including Secretary of State Colin Powell, Vice President Dick Cheney, and Donald Rumsfeld, who was serving as secretary of Defense for the second time in his career. Managing the infighting fell to national-security advisor Condoleezza Rice, who was much younger than the three warring giants and had trouble keeping the peace. The Bush years demonstrated that the NSC is useful so long as the relevant players stay in their lanes and the national-security advisor keeps them in line.

Today, although there is a general consensus about the NSC's advisory role, there are occasional hiccups. Pompeo, for example, revealed in his memoir that the NSC slipped too much into operations during the Obama years. According to Pompeo, national-security advisor Susan Rice acted like

a shadow CIA director, without whose approval no action moved forward. Her knee-jerk dislike for espionage created a verb among CIA officers. Whenever something risky was on the table, someone might say, "No, we can't do that. It will be SR'd." "SR," of course, stands for Susan Rice.

In 2017, the Trump White House raised hackles with its placement of strategist Steve Bannon on the NSC — a move that was reversed a few months later.

These incidents are notable mainly because they violate the current consensus on the proper role of the NSC: that it is a coordinating body that governs decision-making among the collection of national-security offices and departments. The NSC's stability, forged through years of trial and error, has made it the model for other policy councils.

THE DOMESTIC POLICY COUNCIL

The Nixon administration pursued some ambitious goals in domestic as well as foreign policy, but these lacked the guided and orderly nature of Kissinger's NSC. Nixon had a contentious domestic-policy team with several big-name stars competing for primacy, including economist Arthur Burns, Democratic gadfly and intellectual Daniel Patrick Moynihan, and head of the Office of Economic Opportunity Donald Rumsfeld. Managing these powerful personalities required an honest broker; White House lawyer John Ehrlichman emerged to fill that role. In doing so, he became Nixon's key player in domestic policy and helped set the model for domestic-policy management for future administrations.

Ehrlichman wielded significant power. According to Nixon White House aide Edwin Harper, Ehrlichman helped

give the president what he wanted in a policy process, including avoiding presidential involvement in arguments or personal confrontations in either formal or informal meetings, and allowing the president quietly to study his options with input from the advisors he selected, options faithfully and succinctly presented by a neutral broker with a bottom-line recommendation.

Nixon formalized this model by creating a Domestic Council, analogous to and modeled after the NSC, while eliminating the short-lived councils and committees devoted to urban affairs, the environment, and rural affairs. The council included nine cabinet members and met periodically.

The Domestic Council outlasted the Nixon administration, though the name would change. Gerald Ford kept the name, but he also appointed Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, who was more liberal than Ford and his team, to run the council. The decision contributed to Rockefeller's being eased off the ticket in 1976, which may be why no subsequent vice president ever took on the role again. Jimmy Carter's domestic-policy entity, the Domestic Policy Office, was run by Stuart Eizenstat, a member of the so-called "Georgia Mafia" that came with Carter from Atlanta.

In the Reagan years, the council became the Office of Policy Development (OPD), run by Nixon White House veteran Martin Anderson. Anderson used the office to aggressively assert White House control over cabinet policymaking, which was to be based on "notebooks" prepared by Anderson and his team. The notebooks contained Reagan's statements from the 1980 campaign and other venues, and guided policy development. As OMB head Jim Miller recalled:

Anderson's books were the bibles. The president had a consistent ideology. The bibles provided a consistent framework and consistent ideas. I felt I could predict what Ronald Reagan would do in almost any circumstance from the statements in these notebooks.

The OPD maintained seven cabinet mini-councils, in which groups of cabinet members would come to the White House and hash out administration policy. Anderson was particularly fond of the councils, recalling:

The genius of the Cabinet council system was that councils were Cabinet-level. You couldn't send substitutes, such as deputies, to the meetings....What really made the whole thing work was that all meetings had to be in the White House. The White House controlled what time the meeting would take place, where the meeting occurred, and the agenda.

As a result of all this, political scientist Shirley Anne Warshaw concluded that "juxtaposed against the Nixon, Ford, and Carter administrations, the Reagan White House had far more success at controlling departmental policy initiatives and minimizing interdepartmental warfare."

The George H. W. Bush administration was less effective at managing domestic policy. At the top of the White House hierarchy were chief of staff John Sununu and OMB director Richard Darman, both of whom were intolerant of staffers they deemed intellectually deficient and quick to let them know. In fact, the regular process of being berated by Darman in front of the entire White House senior staff became known as "being Darmanized."

Understandably, such behavior rendered staffers wary. This resulted in a perceived paralysis in Bush's domestic-policy agenda. The administration was also overly focused on process. Hanns Kuttner, an aide to domestic-policy chief Roger Porter, was dubbed "the Fontmeister" because of his focus on properly formatting documents. Porter's staff had buttons made up reading "Born to Process."

This weakening of the OPD within the Bush White House resulted in the development of alternative power centers. One of these was Bush's Council on Competitiveness, which sought to include people outside the traditional policy process in policy development and decision-making. Another rump group, which domestic-policy aide Charles Kolb called "the usual suspects," included Jim Pinkerton of what was now called the Domestic Policy Council (DPC), Al Hubbard of the Council on Competitiveness, communications staffer Tony Snow, and John Schall from the Office of Cabinet Affairs. While Cabinet Affairs is not typically part of the policymaking process, Bush's Cabinet Affairs shop included some talented and eager staffers who propelled it to fill some of the domestic-policy vacuum.

The Bush administration also suffered from a lack of clarity. It was hard to sort out among Bush's economic advisors — including Darman, Treasury secretary Nicholas Brady, and Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) chairman Michael Boskin — who was in charge. According to Bob Woodward, Bush himself complained about this, saying: "This is not like the NSC....It doesn't come to me [in a decision memo] saying Brady thinks this, Darman that, Boskin disagrees." The lack of process clarity contributed to the politically damaging perception that Bush was insufficiently focused on the economy during his 1992 reelection bid.

THE NATIONAL ECONOMIC COUNCIL

Bush's loss in 1992 opened up an opportunity to reform the OPD system. The government and the economy had grown such that one council was insufficient to handle it all. Into this mix stepped President Clinton, who promised "to focus like a laser beam on the economy." Part of this laser-like focus included the creation of a new policy council, the National Economic Council (NEC). It aimed not only to demonstrate Clinton's attention to the economy, but to develop a mechanism for sorting through conflicting advice from his advisors. As Clinton wrote in his memoir about creating the NEC:

I had become convinced that the federal government's economic policy-making was neither as organized nor as effective as it could be. I wanted to bring together not only the tax and budget functions of Treasury and the OMB, but also the work of the Commerce Department, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, the Council of Economic Advisers, the Export-Import Bank, the Labor Department, and the Small Business Administration.

During the Clinton administration, the Democratic Party was divided between a more leftist wing, represented by Labor secretary Robert Reich, and a more moderate, business-friendly wing represented by the Democratic Leadership Council. The new NEC was supposed to resolve the differences that arose between those two perspectives.

The idea, as the CEA's Alan Blinder told the New York Times' David Rosenbaum, was to create a situation in which "you're all around the room and the President hears all sides fairly presented and then makes a call, [so] people don't go away grumpy." Thus, Clinton intentionally modeled the NEC on the NSC — specifically the NSC as run by Scowcroft. Despite some internal challenges, the NEC's basic structure has remained in place.

There is a recurring, inherent tension between the NEC and the CEA. The CEA is supposed to give the president economic advice. It is typically staffed by academic economists and headed by a Senate-confirmed chair. The NEC, meanwhile, is supposed to be a coordinating body, distilling recommendations from different advisors and serving as a neutral arbiter of internal disputes. The NEC's head is a more political player, and does not have to be an economist by training. According to the NEC's first director, Robert Rubin, the CEA was supposed to serve as "the hand of economic analysis within the NEC glove."

In practice, this division of responsibility has not always worked. During the George W. Bush administration, the CEA and the NEC clashed frequently. When NEC head Larry Lindsey departed in December of 2002, it was considered a win for the CEA. But the NEC got the last laugh in 2003, when the CEA was exiled from the White House, moved out of the complex from the Eisenhower Executive Office Building to 1800 G Street. White House spokeswoman Ashley Snee downplayed the move as "a space-management issue," but the Washington Post's Dana Milbank called it an end to "the 10-year power struggle between the CEA and the ascendant NEC."

The struggle would continue during the Obama administration. As the New York Times' Peter Baker wrote: "At the National Economic Council, [Harvard professor Larry] Summers was charged with running the process for developing policy. But the team never embraced the no-drama-Obama ethos." Part of the problem was Summers, who, as Baker wrote, was seen by colleagues as "an eye-rolling intellectual bully." Summers had a tendency to fight with the CEA heads and others in the Obama economic operation.

Another tension concerns which council handles international economic issues. This challenge is particularly important today with the need for a coherent approach to China. Although the NSC has long had a senior directorship for international economics, the NEC's purview over economic issues means it has international responsibilities as well. Clinton's original executive order included international aspects of the NEC's mandate, but it did not mention the NSC specifically or state how the two councils were to work together.

Tensions existed throughout the Clinton administration about whether the NEC head should join calls with foreign leaders, whether the NEC should participate in writing briefings for interactions with foreign leaders, how much time should be devoted to economic issues on foreign trips, and who should get to see international-economics briefings before they went to the president. On the last point, the NEC wanted to include all of its traditional stakeholders in economic policymaking, while the NSC was reluctant to distribute its sensitive briefing materials.

The George W. Bush administration addressed the problem with an interesting innovation — dual-hatted staffers with reporting responsibilities to both the NEC and NSC. Bush saw his approach as "a way to make sure the economic people don't run off with foreign policy and vice versa." Bush's well-received innovation has been kept by subsequent presidents of both parties.

Tensions still arose, however. During the first Trump administration, NEC head Gary Cohn regularly clashed with White House aide Peter Navarro, who wanted a tougher stance on America's trading partners. On more than one occasion, Cohn swiped off Trump's desk papers that would have pulled the United States out of existing trade agreements — a breach of process that would be classified as a process foul in any other administration. According to former White House communications director Michael Dubke, Cohn and Navarro conducted their policy process by press leaks, as "there continued to be leaks about one side or the other in order to force the President to make a decision, maybe before he had heard all the arguments." Once again, there needed to be mediation between different factions.

Trump signaled support for Navarro at the start of his first administration, appointing him to a new office called the National Trade Council. This was not a policy council in the traditional sense; according to journalists Yasmeen Abutaleb and Damian Paletta, "the 'council' wasn't so much a 'council' as it was a 'Peter.'" Cohn maneuvered to have the council eliminated and then directed Navarro to report through the NEC. This made it harder for Navarro to participate in key decision meetings, but it irked Trump, who would ask, "Where is my Peter?"

The problems in the Trump administration do not indicate that the NEC's role in economic affairs is unmanageable, however. The lessons to be learned are different. First, Cohn's fights were with the Trade Council, not the NSC, suggesting that the dual-hatted NEC-NSC staffers are still effective. Second, the Trade Council itself was newly designated, a reminder that creating new White House policy entities can be costly. Finally, the Trump administration had a propensity for internal conflict, based in part on Trump's own declaration: "I like fighting."

The process can work if a president is committed to it. I. M. Destler, an academic who has studied the NEC process, observed that "the NEC's effectiveness will ultimately rest on how it connects with the president's decision-making style and his inner political circle. Process regularity can go only so far unless the president himself accepts some discipline."

THE HOMELAND SECURITY COUNCIL

Though there had been movement toward creating a council to address domestic emergencies, the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks precipitated George W. Bush's creation of the Homeland Security Council (HSC) on October 8, 2001. Bush's vision was even more explicitly based on the NSC than the DPC or the NEC had been. It would be run by an assistant to the president who had cabinet rank but no need for Senate confirmation. It would have 120 staffers — fewer than the NSC, but about four times as many as the DPC or the NEC. It initially had coordinating responsibilities for 40 government departments and agencies, though that number was consolidated when the Department of Homeland Security was created by statute in November 2002.

In the years since its creation, the HSC has more closely resembled early incarnations of the DPC, with its name changes in multiple administrations, than the NEC, which has been relatively stable since its 1993 creation. Bush divided the roles of the NSC and the HSC using a fairly clear delineation between international- and domestic-security threats, somewhat analogous to the division of responsibilities between the CIA and the FBI. This meant that the HSC not only exchanged elbows with the NSC, it also butted heads with the DPC and the NEC.

The Obama administration moved away from the HSC concept. Four months after he took office, in May 2009, Barack Obama subsumed the HSC within the NSC. He created a single entity called the National Security Staff (NSS), which included both NSC and HSC responsibilities. The NSS was tasked with "support[ing] all White House policy-making activities related to international, transnational, and homeland security matters." At the top of this new organization was still a national-security advisor, James Jones, which meant that the lead homeland-security advisor, John Brennan, had to report through Jones. Despite being sold as a merger, the action was really an NSC takeover of the HSC.

Thus began a series of revolving-door moves in which the Trump administration separated the two entities and the Biden administration merged them back together. It's unclear if one approach is better than the other, but shifting responsibilities between administrations damages continuity and creates confusion over roles and responsibilities.

During the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, critics of the Trump administration derided its decision to eliminate the biodefense directorate. Trump advocates countered that it still existed, but was housed in a more rational place. Regardless of who was right, having one coherent and continuous institution for handling biodefense issues optimizes our ability to respond to biological threats, while pendulum-like change degrades it. Most of the people responsible for responding to these challenges are career officials who serve in both Democratic and Republican administrations. Periodically changing the reporting structures only creates confusion when we most need clarity and efficiency.

THE GENDER POLICY COUNCIL

In March 2021, President Joe Biden established a Gender Policy Council (GPC). This new council would be headed by an assistant to the president — former Hillary Clinton aide Jennifer Klein — and have 36 members, including national-security cabinet offices like the secretaries of State and Defense and the director of national intelligence. The latter was tasked with designating "a National Intelligence Officer for Gender Equality, who shall coordinate intelligence support for the Council's work on issues implicating national security." As with the other domestic councils, its staff is largely comprised of political appointees.

According to White House briefing materials, the new GPC was created "to advance gender equity and equality in both domestic and foreign policy development and implementation," and was therefore given coverage over "a range of issues — including economic security, health, gender-based violence and education — with a focus on gender equity and equality, and particular attention to the barriers faced by women and girls." Klein explained the perceived need for the GPC:

All these issues are issues of human rights, of justice and of fairness, but they're also critically important, strategically. If you care about reducing poverty or promoting economic growth, increasing access to education — really any outcomes that we seek — you care about these "women's issues."

The GPC was an expansion of Executive Order 13506, issued by President Obama in 2009, which created the White House Council on Women and Girls. Both executive orders were modeled after those creating the OPD and the NEC. Despite the similar language, the GPC does not fit the model of the other policy councils, specifically the DPC and NEC. Most of its issues fall into the DPC ambit, resulting in overlapping jurisdictions.

The GPC is designed to be a political football. Going forward, Republican administrations will likely disband it, and Democratic administrations will resurrect it. The Biden team clearly considers the inevitable dissolutions of the council under GOP administrations and the resulting negative press coverage features, not bugs.

Making the GPC equivalent to the traditional policy councils poses problems. The issues the GPC is tasked with addressing are already in the purview of one of the existing policy councils, which will likely lead to unnecessary turf wars. Also, by establishing a council based on a constituency rather than a traditional policy area, the GPC drifts into the purview of the Office of Public Engagement. This raises the possibility of other platform-driven policy councils in subsequent administrations — a prospect that would only further degrade the policy process.

UPHOLDING A LEGACY

At some point, the proliferation of policy councils becomes an impediment to getting things done. Additionally, the creation and dissolution of policy councils based on the ideological sentiments of the incoming team undermines the White House policy process itself, replacing the bipartisan tradition handed down from administration to administration with a partisan operation that changes based on the preferences of a particular president.

The White House policy process is a delicate organism that should not be reengineered on a whim. Its traditions and established procedures developed over time, and usually for good reason. Even when new creations, like the NEC, eventually proved effective, their success required fighting along the way.

Consistently rearranging council responsibilities leads to slow, poor, and negligent responses to challenges and emergencies. Presidents have the authority to reorganize the White House and create new policy councils, but that doesn't mean they ought to do so.