The Neo-populist Economic Consensus

We're told we live in extraordinarily divided times. And yet, even now, a new economic playbook — one largely skeptical of free-market orthodoxy — holds much sway over both Republicans and Democrats in Washington, D.C. That playbook has helped pull together bipartisan coalitions of lawmakers and executive actors who are passing legislation and enacting regulations on issues related to fiscal policy, government spending, trade, competition, and more.

Hints of this development first materialized during the 2016 presidential primaries, when the historically pro-free-trade Republican Party selected Donald Trump, a vocal opponent of trade liberalization, as its nominee. Prominent Republican senators elected since then — such as Missouri's Josh Hawley and Ohio's J. D. Vance — have helped carry the trade-barrier torch into 2025. President-elect Trump, now poised to take on a second term, has already threatened to hike tariffs on imports from Mexico, Canada, China, and others.

On the left, anti-market voices have long been influential. But again during the 2016 Democratic primary, a major shift occurred when socialist Bernie Sanders pressured Hillary Clinton to flip against the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a trade agreement she had helped negotiate and once called "the gold standard of trade deals."

Acknowledging the emerging overlap between the market-skeptical right and left in an April 2023 speech, Biden national-security advisor Jake Sullivan referred to a "new Washington consensus." While Sullivan's speech lacked much policy detail, it's hard to deny that policymakers from both parties have departed from the consensus outlined by the late British economist John Williamson in 1989. That consensus defined what became known as "neoliberal" economics, which spread throughout much of the world during the latter part of the 20th century. The 10 principles Williamson identified included:

1. Fiscal-policy discipline

2. Redirection of public spending from subsidies toward pro-growth sectors

3. A broadening of the tax base and reductions in marginal rates

4. Market-determined interest rates

5. Competitive exchange rate

6. Trade liberalization

7. Liberalization of inward foreign direct investment

8. Privatization of state enterprises

9. Deregulation

10. Legal security for property rights

To varying degrees, consistency with the neoliberal consensus can be seen in the economic-policy agendas of the Reagan, George H. W. Bush, Clinton, George W. Bush, and Obama administrations.

Over time, both parties have abandoned nearly all of these positions. The new consensus that has emerged — David Leonhardt of the New York Times called it "neopopulism" — consists of something like the following 10 principles:

1. Reorientation of fiscal policy toward national goals amid accumulating structural deficits

2. Progressive and pro-family taxation

3. Central-bank-determined interest rates with inflation targets

4. Flexible, market-determined exchange rates favoring weaker currencies

5. Trade barriers and tariffs

6. Capital-inflow controls

7. Industrial policy

8. Bailouts

9. Policymaking via the administrative state

10. Aggressive antitrust-law enforcement

At times, proponents of the neo-populist consensus appear to ignore economic theories and empirical research that support neoliberal principles. They can also overlook the fact that economic-policy decisions entail tradeoffs to be examined and weighed against one another. Instead, many focus on the political message, with both parties' candidates competing for votes via unrealistic spending and taxation promises.

Despite its shortcomings, the neo-populist consensus may now be entrenched. For those who believe that markets and incentives are powerful mechanisms that can deliver prosperity for Americans of all incomes, the objective now must be to redirect neo-populists' impulses in a more neoliberal direction while championing their best ideas.

FISCAL NATIONALISM AND ACCUMULATION OF DEFICITS

John Maynard Keynes taught that fiscal policy should be tightened during good times so that it can be expanded during difficult ones. Unfortunately, the logic of that view seems to have been lost on political leaders in recent decades. Rather than expanding and contracting federal spending in tandem with economic cycles, these officials have piled on additional structural deficits in both good times and bad.

America's fiscal-policy discipline has been eroding since the end of World War II, but in recent years, it has collapsed. Post-pandemic, the ratio of federal debt held by the public to GDP has flirted with the 100% threshold, thanks in large part to the $2.2 trillion CARES Act of March 2020 and the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan (ARP) of 2021. One could argue that these pandemic-era fiscal-relief packages were less a stimulus than a form of social insurance designed to offset the lockdowns' negative effect on incomes. But once the economy began to stabilize after the second quarter of 2020, it became clear that the ARP was not needed to replace lost earnings.

Even after the pandemic receded, America continued to run massive fiscal deficits. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022 — laden with electric-vehicle subsidies and other features of the infamously expensive Green New Deal — demonstrated little commitment to long-term fiscal sustainability. The same was true of President Joe Biden's unilateral attempt to implement blanket student-loan debt forgiveness at an estimated cost of $870 billion.

Given the increasingly untethered spending that has occurred in recent years, the rise in inflation that began in 2021 should have come as no surprise. Some analysts blame pandemic-related supply-chain disruptions for the uptick, but recent analysis from William Kinlaw, Mark Kritzman, Michael Metcalfe, and David Turkington suggested that at least some of the inflation that occurred was related to fiscal stimulus and the growth of the money supply. In truth, as Ben Bernanke and Olivier Blanchard find in a study to be published in the American Economic Journal, both trends likely contributed to the problem: When reduced supply from Covid-19 supply-chain disruptions met increased demand induced by federal fiscal policy, we experienced a burst of inflation.

This development helped settle a debate among economists on long-run economic growth: We now have solid evidence to suggest that sclerotic growth is not necessarily the result of demand-side "secular stagnation" that can only be fixed through massive fiscal and monetary stimulus; it is rather a supply-side problem. To increase supply, we need to implement policies that increase the economy's productive capacity — either directly or by reducing costs.

On the cost-reduction front, tackling major entitlement programs like Social Security and Medicare — which account for a significant and rising portion of the federal debt — remains the ultimate political taboo. Instead, neo-populists ranging from Donald Trump to Bernie Sanders have sought to cut costs in part by ending expensive wars overseas. Yet U.S. defense spending as a fraction of GDP is at 2.7% — down from its recent peak of 4.5% during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and significantly lower than its peak of 8.6% at the height of the Vietnam War. It's not clear how much further defense costs can be cut — especially given the major conflicts that erupted throughout the world during the Biden presidency.

Depending on the future path of inflation and interest rates, keeping government debt levels and related interest expenses under control could pose a significant challenge for policymakers of the 21st century. That said, we are beginning to hear a chorus of voices on the right push for cuts to government spending for the first time in nearly a decade. The coming reconciliation tax-reform bill will likely repeal provisions of the IRA — particularly the electric-vehicle subsidies. There is also hope that new initiatives, including the Department of Governmental Efficiency (DOGE), will bring about significant reform and substantial reductions in government spending.

PROGRESSIVE AND PRO-FAMILY TAXATION

Under the old neoliberal consensus, policymakers focused on reducing marginal tax rates to increase incentives to work. Adages like "lower the rates and broaden the base" dominated the conversation. Top marginal rates in the United States dropped from 70% in 1980, when Ronald Reagan took office, to 28% when he left. At the same time, some policymakers pushed for single-rate flat-tax schedules with initiatives like Robert Hall and Alvin Rabushka's flat-tax plan in 1985 and, more recently, the fair-tax proposal.

Decades later, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act — passed by a Republican-led House and Senate and signed into law by Republican president Donald Trump — reduced the top marginal tax rate by a mere 2.6%. The days of base-broadening individual tax cuts are clearly over.

In a break with Republican platforms of the past, many tax policies that neo-populist Republicans advocate are less about taxation per se and more about shoring up the American family. For instance, in 2022, as an alternative to the ARP's temporary expansion of the child tax credit, Senator Mitt Romney introduced a plan to give every family a monthly benefit of up to $350 per child for children ages five and under and $250 per child for those ages six to 17. While running for vice president, Senator J. D. Vance proposed raising the credit to $5,000 per child and extending it to all American families. Kamala Harris proposed a similarly sized child tax credit for families with newborns during her 2024 campaign.

This shift in attention to the family is arguably welcome in an era where birth rates are declining in advanced economies the world over. That said, while policies like child tax credits sound nice, it's not clear that they will revive birth rates in a culture where there are increasing social pressures against having children. What's more, child tax credits skew toward subsidizing the upper-middle class. Baby bonuses — that is, direct payments to families upon the birth of a new child — would likely be more effective at promoting fertility more broadly than expanded tax credits.

Though the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act — key parts of which are up for renewal this year — took a smaller swing at individual tax rates than Republican-supported measures of the past, it did contain substantial pro-growth elements. Notably, it reduced the corporate tax rate from 35% (then one of the highest in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) to 21%. It also likely raised fixed investments and mitigated losses in corporate-tax revenues, which have now reached percentages of GDP (around 1.6%) that are higher than they were when the legislation was first implemented. During his 2024 campaign, President-elect Trump pledged to reduce the corporate-tax rate further, to 15%, in what would be another victory for economic growth. Given that some evidence suggests corporate tax cuts are more pro-growth than cuts to individual rates, these efforts should give holdouts of the neoliberal consensus some relief.

That said, although economic growth helps alleviate public-debt problems, growth rates are lower today than they were in the aftermath of World War II. Assuming the individual income-tax provisions in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act are kept or expanded, renewing the act will almost surely contribute to the deficit, as will following through on Trump's campaign promises of adopting larger child tax credits, removing taxes on tips, and the like. The ultimate challenge for Republican policymakers going forward — at least for those who wish to avoid courting fiscal disaster — will be to offset any additional tax cuts and credits with significant cuts to government spending. Repealing provisions of the Biden-era IRA would be a good start; adopting far-reaching structural reform could get us much further.

Such efforts will face strong opposition from Democrats, who prefer to increase federal spending in an attempt to transform America into a European-style welfare state. Some, like Vice President Kamala Harris, have said they would do so without raising taxes on the middle class. At some point, however, Democrats will be forced to grapple with the fact that there simply aren't enough high-income individuals in the United States to fund the expansive welfare state they have in mind — meaning that those who wish to continue increasing government spending will have to consider raising taxes on the population more broadly.

INTEREST AND EXCHANGE RATES

In the 1970s and '80s, there arose a contentious debate over monetary policy. This was due in part to the culmination of a larger debate that took place during the Bretton Woods fixed-exchange-rate era of the 1950s through the 1970s, which focused on whether floating or fixed exchange rates were optimal for the economy. Milton Friedman, a champion of neoliberalism, fought for floating exchange rates, while Robert Mundell favored fixed-exchange-rate regimes. Friedman and floating exchange rates ultimately won out with the demise of the Bretton-Woods fixed-exchange-rate system in 1971.

Toward the end of the 1980s, after the Paul Volcker-led Federal Reserve tamed inflation, the debate shifted to the question of whether central banks should target monetary-growth rates to maintain price stability. The Federal Reserve did so until it realized that such a task was excessively difficult given the unstable nature of the demand for money. Shortly thereafter, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand introduced the concept of inflation targeting — maintaining price stability by setting inflation-rate goals. The subject of monetary-growth rates was quickly dropped.

With the strategy debate settled, economists' attention shifted to the inflation target that central banks would choose. Though neoliberals like Volcker and John Crow (then the governor of the Bank of Canada) favored 0% inflation targets, 2% targets eventually won out. Ever since then, the 2% target has been adopted by central banks around the world.

By many measures, inflation targeting has successfully anchored inflation expectations by credibly signaling that the Federal Reserve will do what it takes to return inflation to its long-run goal of 2%. While challenges have arisen, inflation targeting using interest-rate policy tools has become a staple of central bankers since the neoliberal consensus held sway.

Neo-populists on both the left and the right take different approaches to interest- and exchange-rate policy. Whereas the generation of neoliberal Republicans that included Austrian-school adherents like Rand Paul, Steve Forbes, and Judy Shelton represented inflation hawks and a desire to return to the fixed exchange rate of the gold standard, the neo-populist Republicans of today prefer to maintain the flexible interest- and exchange-rates regime. With respect to interest rates, neo-populist Republicans are far more dovish than the neoliberal generation that lived through the Great Inflation of the 1970s and 1980s; President Trump, for instance, criticized the Federal Reserve in 2018 for preemptively raising interest rates to combat inflation.

Meanwhile, on the left, well-funded organizations like the Groundwork Collaborative and politicians like Senator Elizabeth Warren are promoting the idea that corporate profiteering is to blame for inflation, and that the government should combat this behavior with an excess-profits tax.

As for exchange rates, the "strong dollar" doctrine long favored by neoliberals has been upended by neo-populists, who argue the United States should weaken the dollar to increase exports and narrow the trade deficit. In 2019, Republican senator Josh Hawley and Democratic senator Tammy Baldwin introduced the Competitive Dollar for Jobs and Prosperity Act, which would have done just that through a tax on foreign investments.

Though a weaker currency would certainly support exports, it's not clear that running a trade deficit is inherently harmful. Suggesting that the United States depreciate its currency until it closes the trade deficit is an extreme position that would almost certainly trigger another round of inflation — something no one wants.

TRADE BARRIERS AND TARIFFS

Trade liberalization was another key component of the neoliberal consensus that has since fallen by the wayside with the rise of neo-populism.

Following World War II and the disastrous Smoot-Hawley tariffs of the 1930s, the United States shifted toward a more open trading system. In 1947, 22 countries joined U.S. President Harry Truman in signing the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, which reduced or eliminated tariffs, quotas, and other trade barriers among the signatory nations. Then, beginning in the 1980s, presidents of both parties (with support from bipartisan majorities in Congress) negotiated an additional series of regional and bilateral free-trade agreements, ranging from the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) to the TPP. In 1995, the World Trade Organization (WTO) was established to set, enforce, and adjudicate a rules-based international-trade order, helping to ensure that trade would flow as smoothly and freely between countries as possible.

This reduction in trade barriers contributed to broad economic prosperity. Economists Gary Clyde Hufbauer and Lucy Lu of the Peterson Institute for International Economics report that trade liberalization and related technological change raised per-household GDP in the United States by about $18,000 between 1950 and 2016. At the same time, however, increased competition from countries like China and India, combined with technological innovation and the outsourcing of labor to those same countries, contributed to dramatic employment losses in the American manufacturing sector. At its peak in 1979, manufacturing-employment numbers reached 19.6 million. By 2019, that number had plummeted 35%, to 12.8 million.

Mass job losses and burgeoning discontent in the Rust Belt states triggered a tidal shift in the American political economy, helping usher in the first Trump administration in 2016. Whereas Republicans such as John McCain and Mitt Romney had embraced the neoliberal consensus on trade, candidate Trump spoke out against globalization, criticized NAFTA and the TPP, and promised to impose heavy tariffs on various countries. Later, as president, he levied tariffs on thousands of Chinese imports — from raw materials like steel and aluminum to finished products like dishwashers and TV cameras. The Biden administration largely kept these tariffs in place, and even expanded them in some cases. Though the tariffs on Chinese goods could be defended as deterring the Chinese Communist Party from invading Taiwan (among other national-security objectives), Biden also raised tariffs on imports from allied countries like Canada.

Meanwhile, the international trade-dispute system has largely broken down. Back in 2002, after President George W. Bush placed tariffs on imported steel, the WTO came out against the tariffs, arguing that they violated America's WTO tariff-rate commitments. The organization prepared to enact more than $2 billion in sanctions against the United States — then the largest penalty ever imposed by the WTO on a member state. Bush dropped the tariffs the following year.

Today, by contrast, any country can label almost any trade dispute a national-security issue, which leaves multilateral institutions powerless. The complete lack of appetite for rules-based trade policy in our time renders an organization like the WTO largely inert.

Trump's reelection last November and renewed calls for raising tariffs might drive some neoliberals to despair. Though their concerns are valid, they would do well to consider the possibility that tariff threats may result in trade agreements that are reciprocal and more open than they were before 2016. They might also want to consider the potential gains to be made from promoting non-economic objectives through trade policy. While tariffs and sanctions may cause short-run economic harm, preventing the escalation of conflicts throughout the world — whether it be a Chinese invasion of Taiwan or Iranian meddling in the Middle East — may improve our economy in the long run.

CAPITAL-INFLOW CONTROLS

In our post-Bretton Woods era, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is broadly responsible for carrying out three tasks: providing macroeconomic and financial advice to member countries through its annual Article IV consultations, acting as a lender of last resort, and assisting governments in implementing sound financial policies. Thanks to neo-populism, much of the way it carries out these tasks is changing.

In its Article IV consultations, the IMF long favored the free flow of capital across international borders — a strategy preferred by advocates of the neoliberal consensus. This is no longer the case, however, as the IMF has deferred to some empirical findings suggesting that controls against "hot" capital inflows — short-term cross-border investments that take advantage of interest-rate differences or market fluctuations — can lead to more stable economic outcomes.

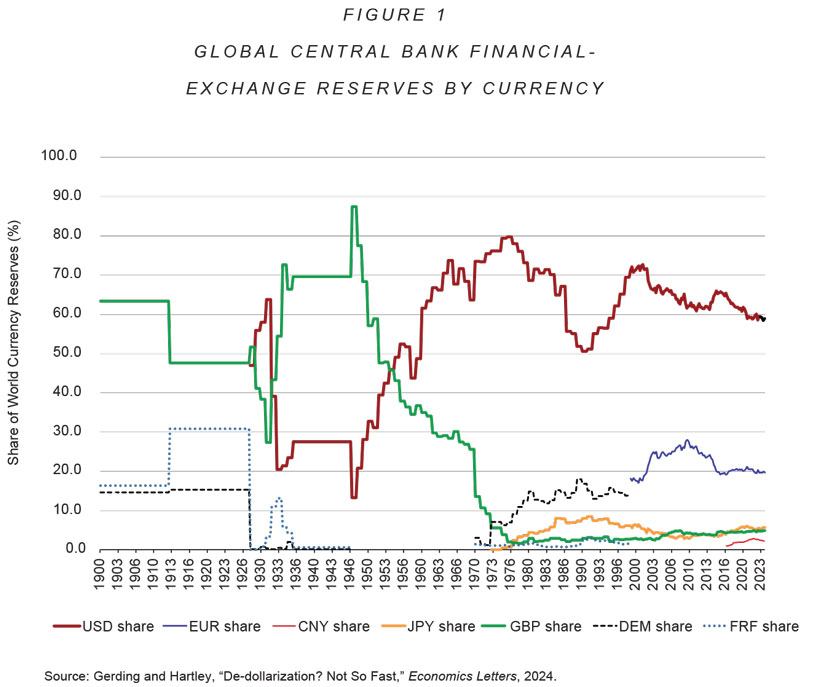

Part of the motivation for this shift is also political in its attempt to integrate more countries into the IMF fold. The IMF took a significant step toward this end in 2016, when it allowed the Chinese yuan to enter its Special Drawing Rights basket of currencies. Such changes arguably represent an attempt to thwart moves by other world players, such as the BRICS Development Bank (now called the New Development Bank), to build a multi-polar currency world. So far, BRICS's attempts to subvert the U.S. dollar have failed, as its shares of central-bank currency reserves, foreign-exchange transactions, trade, and the denomination of global debt securities remain dominant (see Figure 1). However, the BRICS threat still exists, and President-elect Trump has communicated his desire to fight it through trade-policy levers.

On other fronts, the IMF has experienced something of a mission creep. The development of vehicles like the Resilience and Sustainability Trust — which focuses on addressing "longer-term challenges" like combatting climate change and preparing for pandemics — entails significant macroeconomic risk. These sorts of programs fall outside the IMF's area of expertise and divert dollars away from its traditional lender-of-last-resort capacities.

The neo-populist left, meanwhile, continues to push for reforms of the conditions that the IMF attaches to its loans. The IMF's lending has always been conditional — that is, each tranche of IMF support is lent separately as the borrowing country changes its ways over time. Conditions often come in the form of austerity and market reforms, which tend to be unpopular among borrowing-country subpopulations that face no other choice for sovereign borrowing. Socialists like Columbia University economist Joseph Stiglitz have called on the IMF to loosen these conditions — an effort that would almost certainly slow countries' progress in getting their fiscal states in order.

The IMF should resist pressures to expand its mission and to relax its loan conditions. Instead, it should focus on its original duty of acting as a global lender of last resort and promoting broad-based, inclusive, long-run prosperity for all.

INDUSTRIAL POLICY

Both Democrats and Republicans now tout industrial policy as an effective approach to restoring America's manufacturing sector and reviving economic growth. Two major examples include the semiconductor subsidies contained within the CHIPS and Science Act — which received support from bipartisan majorities in Congress — and the electric-vehicle subsidies in the partisan IRA.

Both measures have since run into challenges. The construction of TSMC semiconductor factories in Arizona — subsidized by the CHIPS and Science Act — has been delayed in part because of a lack of skilled workers. Subsidizing the construction of such facilities in neighboring countries like Mexico, which has a labor force and rules more akin to those of Taiwan, could very well be faster and more cost effective.

On a similar note, the IRA's electric-vehicle subsidies were met with an immediate increase in the price of such vehicles. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 contained subsidies for expanding electric-vehicle-charging infrastructure; so far, only a handful of charging stations have been built. Electric-vehicle demand also seems to be slowing globally, posing further challenges.

Industrial subsidies are not some kind of elixir for middle-class prosperity, nor do they promote economic growth. As neoliberals like Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman taught us, no single person or group has access to the sort of comprehensive, particularized, real-time knowledge that would enable them to consistently allocate funds to the right industries and firms at all times. Free markets, by contrast, use the price system to ensure that the laws of supply and demand dictate where capital is allotted, thereby promoting efficiency and, in turn, economic growth.

Industrial policy is also inherently prone to two problems, as economist Glenn Hubbard recently pointed out in these pages. These include mission creep — whereby state officials gradually expand the goal of a given policy to serve their own interests — and rent seeking, whereby firms look to influence policymakers or manipulate economic conditions in their favor. Both problems sacrifice the nation's economic efficiency to promote the interests of the few.

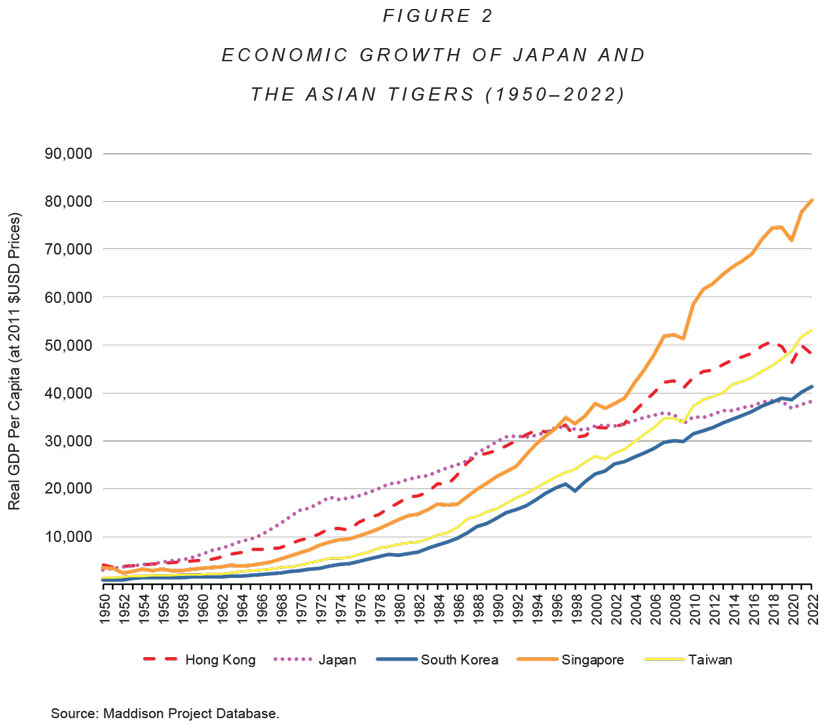

There have been rare instances in which state-led industrial policy has not ended in economic downturns — namely in South Korea and Taiwan. And yet, these success stories likely occurred only because Koreans and the Taiwanese tolerate government-enforced wage suppression and industrial policy that disfavors workers. Given the two nations' robust regimes of property rights and light-touch regulation, such countries may very well have grown economically in spite of their industrial policies. One might also argue that South Korea's industrial policy was more about subsidizing human capital and education than shoring up its domestic industries.

Japan's example is more typical. At its peak between 1949 and 2001, the nation's Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) ran much of its industrial policy. Economists like Richard Beason and David Weinstein have since found that the MITI's policies failed to produce economic growth. The data bear this out: Among Japan and the "Asian Tigers," the countries that implemented industrial policy during the latter half of the 20th century (Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan) achieved lower levels of GDP per capita relative to the countries that did not (Hong Kong and Singapore).

The bottom line here is that industrial policy is a recipe for economic inefficiency, if not disaster. While industrial-policy tactics may have some value when used to achieve non-economic objectives — such as pursuing national-security interests amid renewed great-power competition or obtaining ventilators and personal protective equipment during a global pandemic — they can hardly be taken seriously as a strategy to promote economic growth and opportunity. As Larry Summers recently observed in an interview by the Peterson Institute:

The best generals are the ones who hate war the most but know that it occasionally must be fought; and the best industrial policy advocates are those who recognize just how problematic these interventions are and believe that they should be kept to a necessary minimum to achieve non-economic objectives and not to fall victim to the...fallacy that industrial policy is some kind of...route to prosperity for the middle class.

Unless policymakers are willing to sacrifice economic growth to achieve some greater, non-economic purpose, those hoping to spur the American economy and restore manufacturing and other middle-class jobs would do better to keep the lessons of neoliberalism in mind. In the meantime, neoliberals can take comfort in the possibility of bipartisan permitting-reform efforts that, if adopted, could cut much of the red tape that prevents various industries in the United States from expanding. And of course, we should all have faith in the American promise of technological and economic innovation, which will continue to provide opportunity for Americans in the future.

BAILOUTS

A troubling feature of the international financial system that has emerged since the fall of the neoliberal consensus is the culture of bailouts — a shift that developed well before 2016. In 1984, Continental Illinois suffered the largest ever bank failure in U.S. history when a run on the bank led to its seizure by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). The Federal Reserve and the FDIC infused $1.5 billion into the bank to rescue it, but they could not find a willing merger partner. As a result, the bank and its shareholders were wiped out.

This event marked the beginning of a new culture of bank bailouts that would come to a head during the global financial crisis of 2007-2009. With the assistance of the Federal Reserve, which provided Term Asset-backed Securities Loan Facility financing to firms willing to acquire failed banks, JP Morgan acquired Bear Stearns and Bank of America acquired Merrill Lynch. Additionally, President George W. Bush signed the Troubled Assets Relief Program into law, creating a $700 billion Treasury fund to purchase failing bank assets.

Since the 2008 bailouts, troubling questions remain: Should the banks have been allowed to fail? Why were some banks and their shareholders saved but not others? What sort of risk-taking discipline do bailouts create among banks?

Fortunately, a robust regulatory response involving capital requirements reduced banks' ability to take on leverage, making them less prone to failure. In fact, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act's imposition of capital requirements was meant to permanently deleverage banks. In addition, the act's Orderly Liquidation Authority created a mechanism to wind down troubled financial institutions.

The financial-market volatility of 2020 was perhaps a test of such regulation's effect. Banks ultimately escaped unscathed during the pandemic-induced financial calamity, offering a testament to the success of capital regulation. On the other hand, in 2023, a regional banking crisis emerged amid the Federal Reserve's interest-rate tightening in response to rising inflation. The FDIC's seizure of Silicon Valley Bank with no bailouts for shareholders created the impression that we may be returning to an anti-bailout culture. That said, the FDIC massively expanded deposit insurance to cover essentially all deposits in the banking system. Such blanket deposit insurance may be very costly — perhaps too costly for smaller banks going forward.

Neo-populists who dislike Wall Street and neoliberals who dislike government programs might nonetheless find common ground in developing long-term solutions to the problem of bailouts. One promising area of reform involves the bankruptcy code. Stanford University's John Taylor has suggested adopting a Chapter 14-like provision designed specifically for banks, which would permit failing financial firms of a certain size to go into a predictable, rules-based bankruptcy-reorganization process while leaving their subsidiaries free to serve their customers' financial needs. Such reform could eliminate short-term lenders' incentives to run on the failing institution and prevent disruptive spillovers from harming the economy as a whole.

THE ADMINISTRATIVE STATE

While the neoliberal consensus was decidedly anti-regulation, neo-populists on both the progressive left and the new right see an enhanced role for executive power — albeit for different ends.

Since the time of Franklin Roosevelt, the progressive left has focused on expanding the welfare state and increasing federal control of economic and social activity. Putting this goal into effect has required lawmakers to shift the locus of legislative power from Congress to the executive branch, thereby allowing the president to effectively enact law unilaterally. In doing so, progressives have dramatically increased the size of the administrative state, which now defends progressive policies largely via sclerosis.

The Republican Party has long opposed the growth of the administrative state. Republicans who remain in the neoliberal camp continue to push for broad-based deregulation, with some going as far as to recommend shutting down entire executive departments. Many on the new right, however, are sympathetic to the progressive view of the administrative state, though they have sought to employ unitary-executive theory to take control of it for their own purposes (to pass their own rules related to labor or industrial policy, for instance).

Specific regulations are also increasingly contested between the neoliberal and neo-populist camps. On the neoliberal side, pro-housing-growth Republicans and Democrats want to reduce land-use regulations to increase the stock of affordable housing. In doing so, they hope to provide more housing opportunity in high-productivity metropolitan areas that currently price out low-income individuals. On the neo-populist side, many on the new right are skeptical of wholesale zoning reform, while many progressives want to build more public housing, pass rent control, or expand environmental regulation that slows or even prevents new housing construction.

The first Trump administration was more in line with neoliberals on the subject of regulation; it significantly reduced the number of new regulations issued from administrative agencies and effectively adopted a regulatory budget. With the Supreme Court's overturning of the Chevron doctrine (by which courts were obliged to defer to an agency's interpretation of an ambiguous statute), the administrative state will almost certainly lose some of its autonomy as Trump assumes office once again.

The president-elect's appointment of Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy to lead the DOGE, which seeks to reform the administrative state with inspiration from neoliberals like Milton Friedman and models like Argentina under president Javier Milei, signals that Trump will likely continue to support deregulatory efforts during his second term. One major component of this initiative may include reinstating Schedule F, which would give the executive branch greater discretion in hiring, firing, and managing certain federal civil servants. This move could very well give neoliberals a chance to achieve their objective of enacting sweeping, structural regulatory reform. That said, Congress will have to play a major role in any attempt to reduce spending and could ultimately pose a barrier to such lofty goals.

AGGRESSIVE ANTITRUST-LAW ENFORCEMENT

The late 2010s and 2020s have been marked by a noticeable shift when it comes to competition and antitrust policy. This is primarily visible in the strain of neo-populism that borrows from the views of Justice Louis Brandeis and attacks the consumer-welfare standard.

That standard — best articulated by conservative jurist Robert Bork in his notable 1978 book The Antitrust Paradox — is a legal test that courts have used to adjudicate antitrust claims since the 1970s, when the neoliberal consensus was beginning to coalesce. It calls on courts to determine whether a challenged business merger harms consumers in a relevant market. Generally speaking, as long as a merger does not cause consumer prices to rise, courts will allow it to go forth.

Whereas the consumer-welfare standard recognizes that corporate consolidation does not necessarily harm consumers, neo-Brandeisians argue the opposite. Left-leaning neo-Brandeisians typically focus on promoting the idea that "big is [inherently] bad" and argue that regulators should crack down on corporate profiteering. Those on the right tend to emphasize reducing political power and concentration in Big Tech — an industry seen as hostile to conservative views.

The neo-Brandeisians' rise is not confined to the United States; governments everywhere, including those in Europe and elsewhere in North America, have faced pressure to adopt more aggressive antitrust positions — particularly with regard to Big Tech firms. Such pressure has perhaps been most successful in the case of Europe's General Data Protection Regulation, which went into effect in 2018.

In the United States, antitrust hawks like Federal Trade Commission (FTC) chair Lina Khan have taken it upon themselves to aggressively pursue antitrust cases against major corporate mergers. While these suits drive headlines, the Khan-led FTC has had a poor track record in court — perhaps a testament to how blunt its approach is.

There is some evidence to suggest that antitrust-law enforcement is valuable for sectors of the economy where international competition is weak. One instance dealt with U.S. real-estate agents' commissions, which were about 6% on average — substantially higher than the commissions that agents received in nearly any other developed country. Antitrust authorities in the United States finally persuaded a federal civil jury in Burnett v. National Association of Realtors (NAR) that the association had conspired to inflate commissions paid to home buyers' real-estate agents. NAR and its co-defendants lost the suit and were ordered to pay damages of almost $1.8 billion.

Aside from fines, however, suits against Big Tech companies seldom result in substantive changes; they simply place an undue burden on corporate mergers and waste taxpayer dollars through the appeals process. There have been some exceptions, such as Google's agreement to display choice screens for alternative search engines and browsers in 2018 and 2019. But for the most part, efforts to break up Big Tech have failed.

That hasn't stopped neo-populists on the right from continuing to embrace antitrust-law enforcement against Big Tech, however. Sohrab Ahmari has suggested that the second Trump administration keep Khan in charge of the FTC, while Vice President-elect J. D. Vance has said he'd like to see Google parent-company Alphabet broken up. In December, President-elect Trump signaled support for these sentiments in announcing that he intends to nominate Gail Slater — Vance's former policy advisor — as assistant attorney general for the Justice Department's antitrust division. His statement accompanying the announcement read: "I was proud to fight [Big Tech's monopolistic abuses] in my First Term, and our Department of Justice's antitrust team will continue that work under Gail's leadership."

Neoliberals can take some comfort in the fact that the American judiciary still largely supports the consumer-welfare standard and has blocked most of the Khan-led neo-Brandeisian efforts at the FTC. That said, it might be prudent for courts to consider taking steps to adapt the standard to our new technological age. Many of the traditional industrial-organization models that antitrust policy relies on include a wholesaler who sells goods to an intermediary and a retailer who sells them for some markup price. Technology companies' selling ads for pure profit is not something these models contemplate. Some rethinking of these models may therefore be warranted, but courts should take care not to throw out the consumer-welfare standard entirely while doing so.

THE NEW CONSENSUS AND BEYOND

The neoliberal-consensus framework featured the private sector's taking the lead in the economy, paired with a modest amount of government redistribution. Today's neo-populist coalition, by contrast, seeks a state that increasingly directs spending, regulation, trade subsidies, and more.

How long the coalition will maintain power is unclear. Looking internationally, with some rare exceptions, the progressive left appears to be doubling down on socialism. On the right, the picture is more mixed: While some politicians, like Hungary's Viktor Orbán, champion elements of the neo-populist consensus, there are also rising free-market leaders, ranging from Javier Milei in Argentina to Pierre Poilievre in Canada, who were elected on economic-policy platforms that look a lot more like the old neoliberal consensus.

Stateside, neo-populism may be on the rise, but neoliberalism still holds sway in our governing institutions — including in the U.S. Senate under the leadership of John Thune. Only time will tell which side gains the upper hand in the coming years.